Introduction

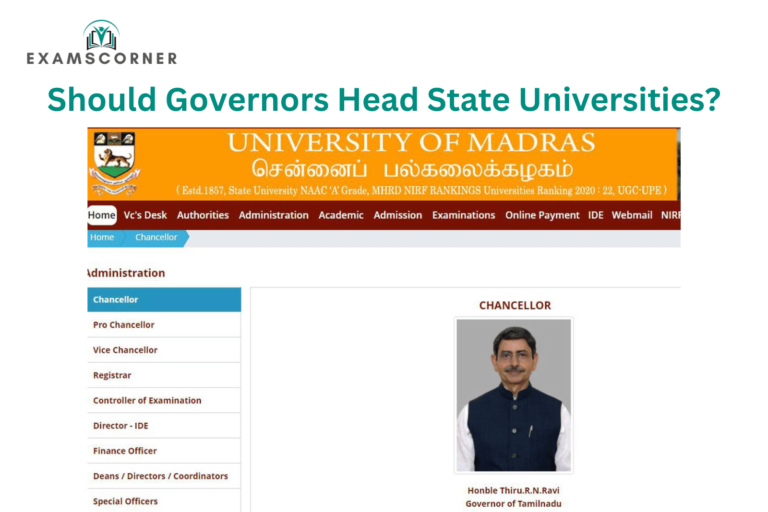

The role of Governors as Chancellors of State universities (Should Governors Head State Universities?) has been a contentious issue in India, raising questions about university autonomy, federalism, and governance. Historically rooted in British colonial rule, this practice has continued post-Independence, often causing conflicts, particularly in States ruled by Opposition parties. Reforming this system has become crucial to safeguard academic freedom and ensure efficient governance.

Historical Context

The practice of Governors heading universities dates back to 1857, when the British established universities in Calcutta, Bombay, and Madras. Governors of the respective presidencies were appointed as ex-officio Chancellors to maintain control. This colonial model was adopted wholesale after Independence without reassessing its relevance in a democratic and federal setup.

Post-1947, the dominance of the Congress party ensured that Governors remained ceremonial figures, with Chief Ministers wielding actual power. However, this changed after 1967, when different political parties began governing States, leading to Governors becoming instruments of the Central government. This shift has often led to politicization, undermining university autonomy.

Constitutional Powers of Governors

The Constitution of India grants Governors a dual role: one as the constitutional head of the State and the other as a statutory authority under various State laws. Key powers of the Governor include:

- Executive Powers: The Governor exercises executive authority on the advice of the Council of Ministers, as per Article 163. This includes appointing the Chief Minister, other Ministers, and key officials.

- Legislative Powers: Under Article 174, the Governor summons, prorogues, and dissolves the State Legislature. They also reserve certain Bills for the President’s assent under Article 200.

- Judicial Powers: The Governor has the authority to grant pardons, reprieves, respites, or remissions of punishment under Article 161.

- Discretionary Powers: In certain situations, such as recommending President’s Rule under Article 356 or reserving Bills for the President, the Governor can act at their discretion.

- Statutory Powers: The Governor’s role as Chancellor of State universities, conferred by State laws, allows them to appoint Vice-Chancellors, nominate members to university bodies, and approve delegated legislation.

While these powers aim to balance the functioning of State governments, their application in university governance has sparked debates on federalism and institutional autonomy.

Challenges of the Current Model

The continuation of the “Governor as Chancellor” model has resulted in several issues:

- Dual Authority: While State governments fund universities, Governors wield significant power without corresponding accountability. This dual authority often results in conflicting demands and administrative paralysis.

- Delays in Appointments: Disagreements between Governors and State governments delay the appointment of Vice-Chancellors, affecting the overall functioning of universities.

- Lack of Expertise: Many Governors lack the academic qualifications or experience to guide educational institutions effectively, leading to questionable decisions.

- Political Interference: Instead of insulating universities from politics, Governors sometimes exacerbate political interference, prioritizing the Centre’s agenda over the interests of the universities.

- Federalism Concerns: Allowing Governors, appointed by the Centre, to control State institutions compromises the principle of federalism. State universities should be accountable to elected State governments.

Insights from Commissions

Various commissions have proposed reforms to address these challenges:

- Rajamannar Committee (1969-71): Recommended that Governors act on the advice of the State government even in their role as Chancellors. However, the Supreme Court has not upheld this interpretation.

- Sarkaria Commission (1983-88): Recognized the Governor’s role as statutory, not constitutional, and recommended consulting Chief Ministers while retaining independent judgment.

- National Commission to Review the Working of the Constitution (2000-02): Advocated for political neutrality, clearer definitions of the Chancellor’s functions, and greater university autonomy.

- M.M. Punchhi Commission (2007-10): Suggested limiting the Governor’s role to constitutional responsibilities and appointing eminent academics or experts as Chancellors.

Alternative Models for Reform

Global best practices provide insights into alternative models that can replace the current system. Some notable examples include:

- Ceremonial Chancellor Model: In this model, the Governor retains a ceremonial role, acting on the advice of the State Council of Ministers. States like Gujarat (1978), Karnataka (2000), and Maharashtra (2021) have adopted variations of this approach.

- Chief Minister as Chancellor Model: West Bengal and Punjab have proposed making the Chief Minister the Chancellor. Tamil Nadu’s 2022 Bill seeks to substitute “Government” for “Chancellor,” but these reforms await Presidential assent.

- State-Appointed Chancellor Model: Implemented in Telangana (2015), this model allows the State government to appoint a ceremonial Chancellor. Kerala’s 2022 Bill suggests appointing distinguished academicians or public figures to this role.

- Elected Chancellor Model: Universities like Oxford and Cambridge empower their university bodies to elect a ceremonial Chancellor. This model promotes institutional self-governance and reduces political interference.

- Council-Appointed Chancellor Model: Universities in the U.K. (Birmingham), Canada (McGill), and Australia (Melbourne) appoint Chancellors through their Executive Council or Board of Governors, ensuring a transparent selection process.

Among these, the State-Appointed Chancellor Model appears most practical for India, provided the appointees are eminent academicians or public figures, excluding politicians.

Dismantling a Colonial Legacy

Reforming the governance of State universities requires a delicate balance between accountability to elected State governments, minimizing political interference, promoting institutional autonomy, and fostering academic excellence. Divesting Governors of their colonial-era role as Chancellors is a vital first step.

While States like Gujarat, Karnataka, Telangana, and Maharashtra have successfully implemented reforms, others such as Tamil Nadu, Kerala, West Bengal, and Punjab face delays due to pending Presidential assent. This highlights the need for impartiality from the President and the Government of India.

Way Forward

India’s higher education system must align with global best practices to promote academic freedom and excellence. Reforms should focus on:

- Limiting the Governor’s role to constitutional responsibilities.

- Appointing eminent academicians or public figures as Chancellors.

- Ensuring university governance models support institutional autonomy.

These measures will dismantle outdated colonial structures and enable universities to focus on their primary mission: fostering education and innovation. The Centre must facilitate these reforms to ensure a progressive and politically neutral higher education system.